I’m no networking geek, but I’d always wished there was a way to link all my devices together. The dream goal would be to always have them within my reach no matter where I am. I have a couple of use cases for this, which include:

- remotely controlling my devices (maybe something like screen sharing or streaming);

- privately accessing self-hosted services; and

- being able to use my devices as if I were there in front of them.

Tailscale has been the key driver to making my set-up work (well, even!), so here’s a small post sharing more about Tailscale and share with you some ways I’ve been using it that maybe you can take inspiration from.

The tail at scale

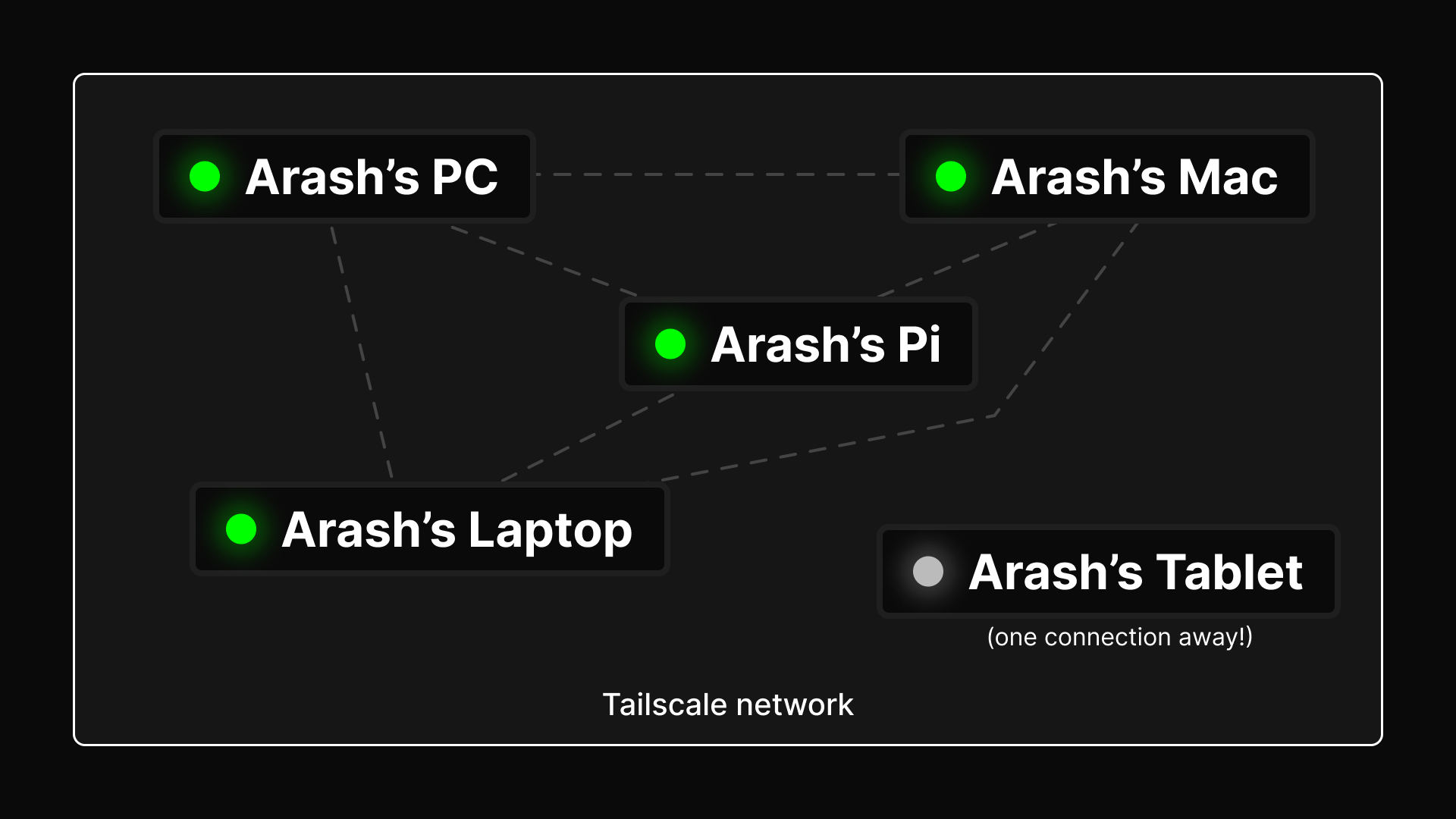

The magic of Tailscale comes from the fact that it creates a mesh network between the devices you set up Tailscale with through a virtual private network. I’ve only ever known VPNs to be used with third-party companies to obscure some part of your network activity through them instead of your ISP, so it’s interesting to see another use case of VPNs here. Believe me, I’m not sure all too much myself about how it works, but I do know that it works so smoothly it’s almost magic.

I can’t seem to remember when I first came across Tailscale, but I remember being fascinated not by the theory and idea, but by its branding (🤡 moment, I know). There’s something about it’s brand identity and its design that makes it 💯 in my impression of it. It’s kinda like me coming across something like the Oxide Computer Company where I fall in love with the design but not understand their offering enough (it’s me, not them).

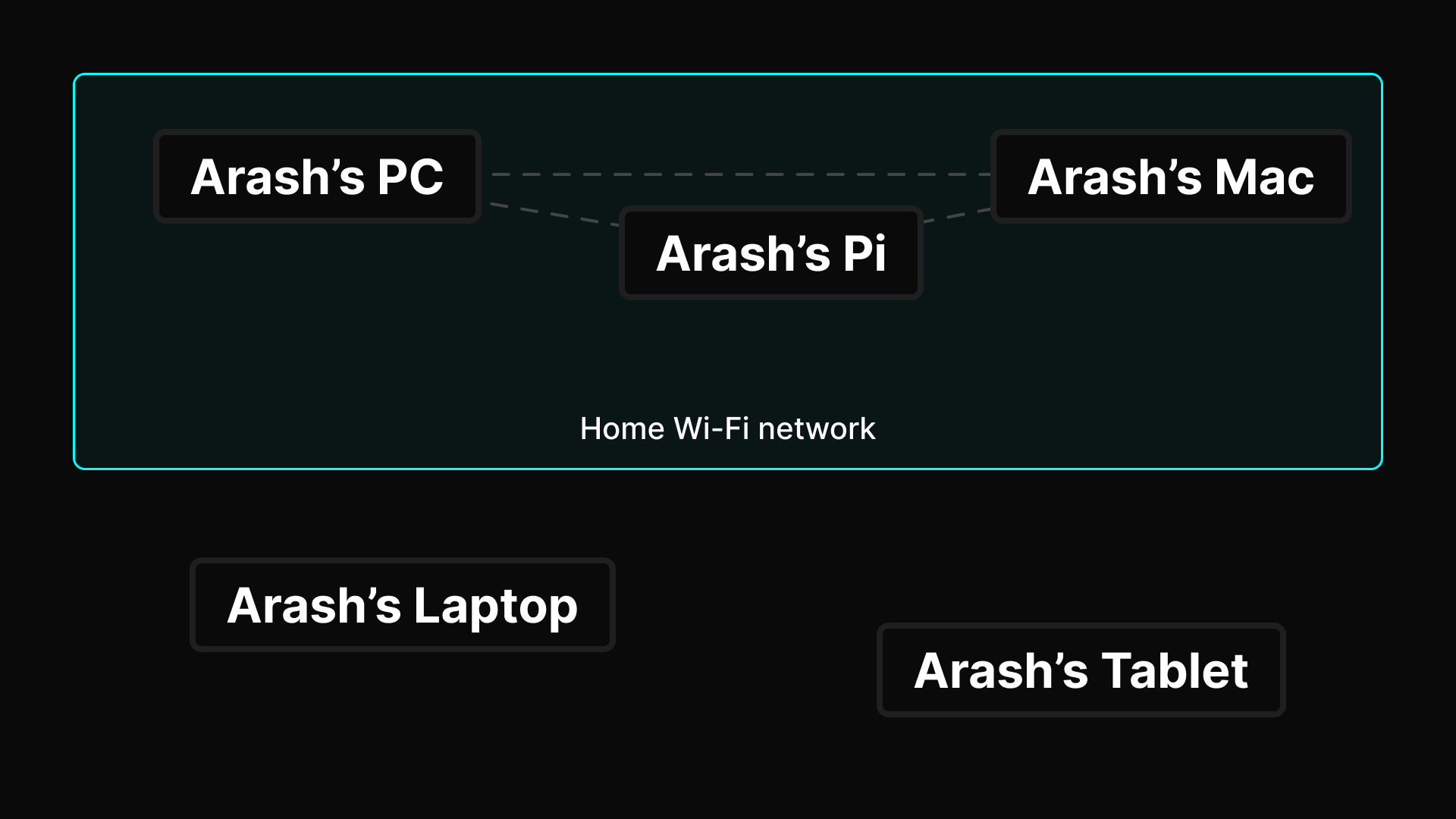

It took me a few visits to their website before I finally started paying attention to the content there, and from there I began to realise it could actually help me a lot by linking my devices together. As it was then, I had a few devices that are separate from each other — the only time they’d be aware of each other and could interact with one another was if they were in the same network, which always was the case at home.

I then began to wonder: would it be possible to make them accessible to each other as they are when they’re in the same network?

Setting up’s the easy part

It’s really easy getting started with Tailscale. All it takes is installing the client app on each of your devices, and you’ll need to access the same common tailnet (their fancy term for network, apparently) by simply signing in through the same credentials. Things are definitely simple enough for my Mac, PC, laptop, tablet, and phone since there are dedicated installers + apps on the respective app stores.

With my Raspberry Pi, as with most things in Linux, an installer script is available, too. I followed their instructions to copy and paste a command in the shell (basically fetching the script then running it) and all’s good to go. Remember, although Tailscale’s a name you can trust, it’s not a bad habit to scrutinise and look through the code of any script you’re running before running them!

The possibilities are endless

So, once you’ve gone through with setting everything up, here’s where the fun begins. As long as your devices are online and connected to your tailnet with the Tailscale clients active, you’ll be able to interact with them just as if you’re in the same network with them. Basically, all the things I wanted to do are now possible! 🥳

Here are some ways I’ve been using Tailscale with my devices. I’ll leave it up to you to determine if they’re cool or not.

Remote SSH

Okay, maybe this isn’t that impressive, but it’s always nice as a dev to be able to access the shells of your devices through SSH. Tailscale isn’t by any means the only way to make your device accessible over the internet via the protocol, but it does so pretty easily with little hoops you need to go through and with reasonable security.

Tailscale natively supports SSH through something called Tailscale SSH, and its premise basically revolves around handling all the auth (both -entication and -orisation) that’s required by SSH connections between devices in the tailnet. Tailscale’s docs on Tailscale SSH is more elaborate than what I can give, but to put it simply: it takes away the pain and confusion that’s needed with making your devices talk to each other pre-SSH session. You just run your ssh command and it works.

Since I have access to the GitHub Student Developer Pack, I’ve been doing everything SSH-related with Termius. It’s a nice ‘do one thing and do it right’ app that does SSH and more (like autocomplete and suggestions!).

The screen’s moving on its own!

Only recently did I start looking at remote screen sharing and control as a way to connect to my devices and control them from afar. Besides, I think it’s a nice flex to friends that you’re able to connect to your home PC if you need any added oompf from your GPU at home than the one on your laptop.

I first started by setting up my PC at home with the Remote Desktop Protocol that Microsoft made available on Windows (Pro) devices. It’s an in-house solution that works surprisingly really well, so I just stuck with it and not opt for other options.

When my internship started around March 2024, I wanted to pick up Swift and Objective-C through making a basic iOS app. Since I have a Mac mini at home, there’s no better time to set up remote access to it! macOS natively supports the Virtual Networking Computing protocol, but it was painfully slow — whatever I typed took ages to show up — so I looked elsewhere. I settled on NoMachine and the NX protocol, and they worked pretty well.

Wake up!

The thing with remote access is that they’re dependent on your device being awake (i.e., not sleeping) to receive the request and respond to it. One simple option to address this is to keep your device on all the time, but I don’t think that looks good because (a) it’s an energy waster and (b) your screen at home will be on and your user account signed in at all times.

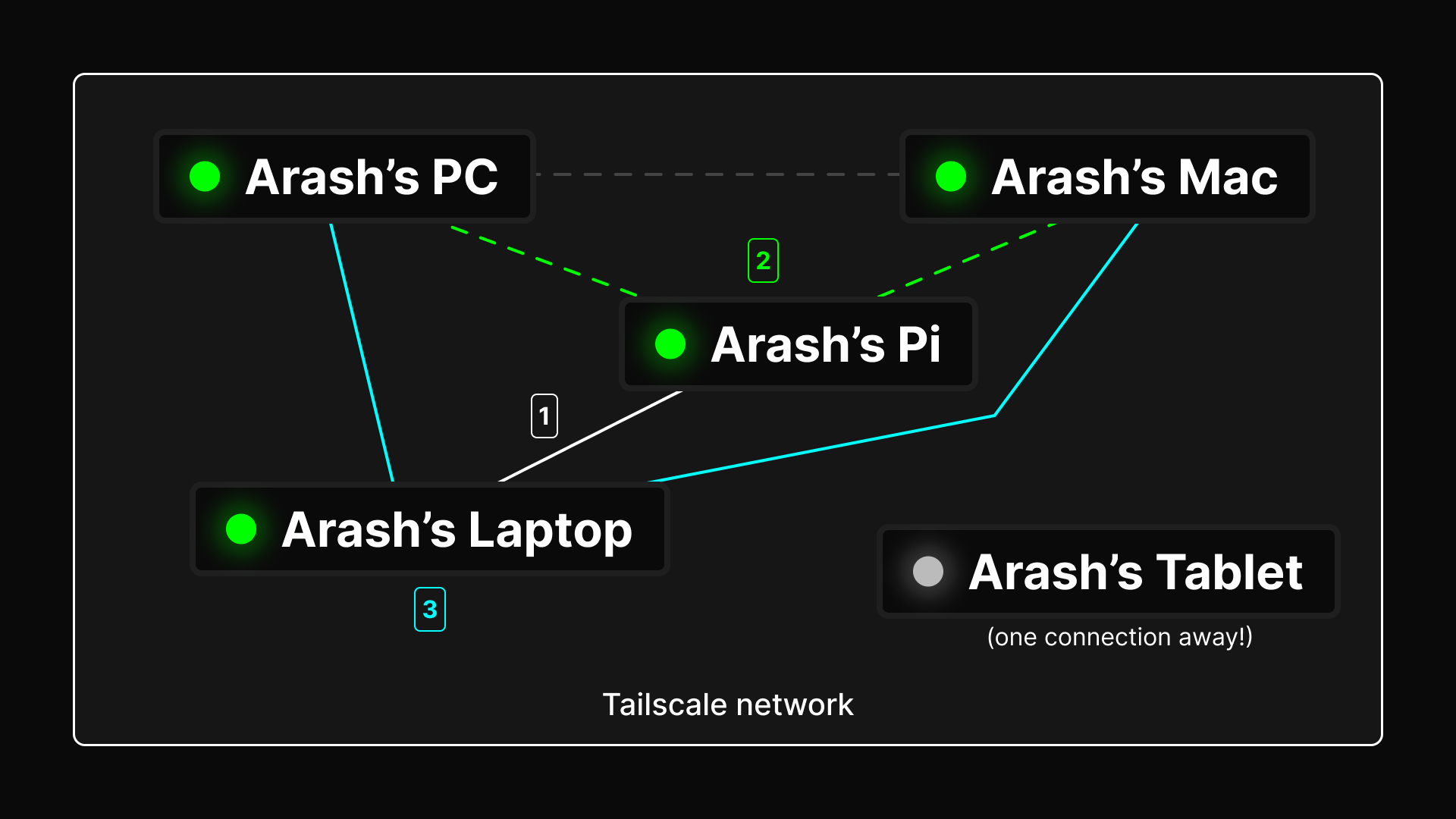

The nifty solution that I opted for is to:

- Connect to my Raspberry Pi and run a command calling a tool to send a magic packet to the right device.

- Wait for the Raspberry Pi to contact and wake up the device. This should take a second or two, not long at all.

- Use the appropriate remote access client (like Remote Desktop Connection or NoMachine) to hop on my PC or Mac.

To do that, I’ll need to:

- Enable magic packet awakening on my PC. I don’t think there an option for this on macOS, but it should support it anyway.

- Install a tool that can send magic packet from my Raspberry Pi, an always-on device.

The tool that I opted for is etherwake. I’ve configured it using .bash_aliases saved in my Pi so that I need to call a single command — wake-pc or wake-mac — to wake the respective device up. Here’s a snapshot of my .bash_aliases file:

alias wake-pc='sudo etherwake -b -i eth0 AA:BB:CC:DD:EE:FF'

alias wake-pc-wifi='sudo etherwake -b -i eth0 BB:CC:DD:EE:FF:AA'

alias wake-mac='sudo etherwake -b -i eth0 CC:DD:EE:FF:AA:BB'

alias wake-mac-wifi='sudo etherwake -b -i eth0 DD:EE:FF:AA:BB:CC'The -wifi commands are there just as a backup, since both my PC and Mac have Ethernet connected to them and are the default for connectivity.

Self-hosting stuff

I mostly use my Raspberry Pi as my little self-hosted server to run light stuff on it. I don’t really run too much there as of now apart from my projects (like Commute and the 5.0 GPA Student), Portainer, and a Joplin server. As with self-hosting things though, projects are gradual and I’ll probably host more things as I gain the confidence to manage them over time!

With Tailscale’s MagicDNS, you don’t even need a TLD to type in when accessing the device. It generates an automatic domain name based off the device (you’re connecting to)‘s name and alters your device (you’re connecting from)‘s hosts file on the go so that you just need to call the machine name to access it. For example, instead of connecting to https://raspberrypi.local:9443 to access Portainer, all I need to do is visit https://raspberrypi:9443 and it’ll do the same thing.

There may obviously be cases where MagicDNS can break the validation of some things that require the domain name format, so it also handily generates a fully qualified domain name that’s basically your machine name + your tailnet name. I’ll then have raspberrypi.my-tailnet.ts.net as the full domain if needed. Super convenient!

To wrap up

To summarise, here are the reasons I love Tailscale:

- 🤩 It’s fuss-free and so simple to set up + configure. Everything major can be done in the web on the admin console, and adding devices to the network is as easy as running an installer to get the Tailscale client working.

- 💰 It’s generous in its pricing. I’ve been using the free tier with no need whatsoever to upgrade to the paid plans because the free plan is just that generous. If you’re working alone or only a person more or two, you can create a tailnet that can work for y’all easily on the free tier.

- 🧠 It simplifies a lot of things. With things like MagicDNS, ACLs, logs, and more, it’s never been easier to manage both the devices in your tailnet and how they’re able to talk to each other.

If all this yapping has you convinced, give Tailscale a try and let me know how it goes for you!